In 1992 the whole AIDS Memorial Quilt was displayed for the next-to-last time on the Mall in Washington, DC. It covered 15 acres. It has gotten much too big since then to be seen all at once. I had lost a good friend to AIDS a short time before and thought going to view the quilt would be a good way to memorialize my friend while recording a little bit of history. So I grabbed my Nikons and headed downtown.

Living in a smaller town an hour away from DC it’s easy to forget how many media professionals work in the nation’s capital. I didn’t expect to see much more than an anonymous sea of faces on the Mall, but hadn’t been in the crowd long before I became aware of a lot of photographers. Not casual shooters, but pros working for news outlets. It took just a glance to tell. They were prowling, moving differently from the rest of the crowd. Some of them seemed in a great hurry, and carried their importance like billowing cloaks around them.

I was feeling pretty laid back and had just begun to take a few pictures with the White House as a backdrop when I heard the burst of a motor drive behind me. I turned around and to my surprise not two feet away stood David Burnett, a photojournalist whose work I had long admired. He had no reason to know me but I recognized him from photos I’d seen. He was taking the same picture I was; moreover he had been shooting over my shoulder because I’d found the shot first. I turned back around nonchalantly but suddenly felt pumped on adrenalin.

I was feeling pretty laid back and had just begun to take a few pictures with the White House as a backdrop when I heard the burst of a motor drive behind me. I turned around and to my surprise not two feet away stood David Burnett, a photojournalist whose work I had long admired. He had no reason to know me but I recognized him from photos I’d seen. He was taking the same picture I was; moreover he had been shooting over my shoulder because I’d found the shot first. I turned back around nonchalantly but suddenly felt pumped on adrenalin.

When David moved away I began following him, feeling a bit like a stalker, but I wanted to watch him work. After a few minutes it seemed we were birds of a feather. He was working calmly but without any wasted motion, and except for his red sweatshirt and expensive hardware seemed to cut a lower profile than some of the other shooters I’d seen. I managed to squeeze off a couple shots of him unnoticed before turning my attention back to the crowd.

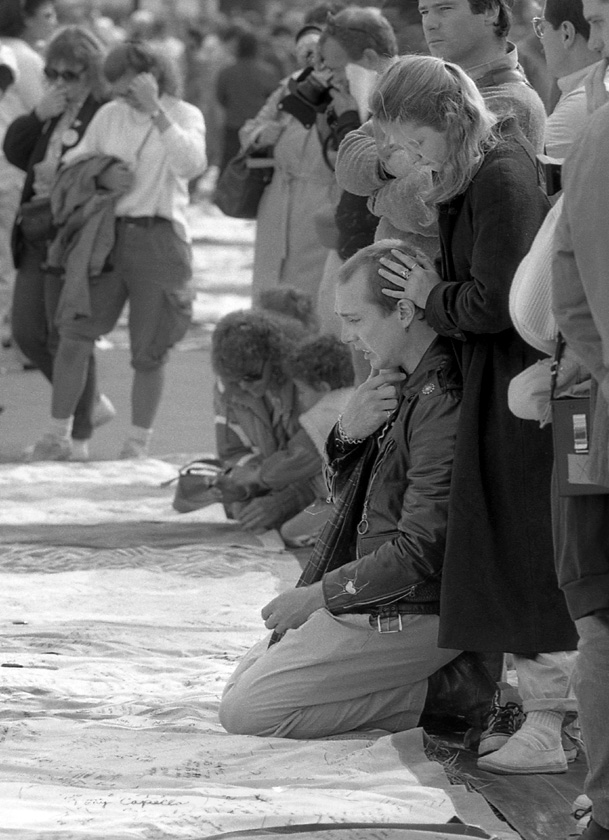

There was a pair of young people quietly grieving at the quilt (photo below) and I paused to take several frames of them. It felt inappropriate to intrude more closely on their privacy so I backed away. Suddenly I was plowed aside by someone moving like a locomotive to occupy the spot I had just vacated. There wasn’t even time to say “excuse me” as a small entourage swept by.

Starstruck

I watched with interest as the woman who had collided with me began photographing the same couple I had just moved away from. Two people were working with her – one was carrying a camera bag and another, a spot meter. She carried only one camera, which allowed her to move freely. When she turned around to speak with one of her assistants I saw her face and got a jolt. The woman was Mary Ellen Mark, one of the world’s most renowned documentary photographers.

Now I was fascinated. David Burnett was a role model to me, a working pro, a concept I could wrap my mind around. But Mary Ellen Mark was a luminary, someone with such a cult following I could hardly separate the person from the legend. Yet here she was before me in the flesh – she had just collided with me, but seemed to take less notice of it than she might a bug on her windshield. Clearly she moved within a different state of being.

Again I moved closer to watch, forgetting about my own pictures. I was intensely curious to see how a legend worked. I’ve seen hundreds of her images – from movie sets to mental wards, from runaways in Seattle to prostitutes in Bombay. I wondered all kinds of things: how she got access to her subjects, how she managed to capture such pathos – often a vulnerability tinged with defiance emerged in some of her more memorable photos – and most of all how she interacted with the people she photographed.

Already I realized how she would get perfect light on a dreary day. No risky guessing with guide numbers and distance – how incredibly cool to have an assistant metering your flash! We all were shooting film back then, and Mary Ellen was using a Nikon FM with a Vivitar flash attached. I also was using FMs, F2s and Vivitar flashes, but the similarities between us ended there, at least on that day.

You’ve got to be kidding me

What I saw next left me disillusioned for some time afterward. Since then I’ve recovered my admiration for Mary Ellen in view of her incredible work ethic, her brilliant eye and most of all her unflinching persistence in showing the humanity of all kinds of people. But on that day she walked right up to the grieving couple I had just backed away from and after a very few words began arranging them into a more pleasing and pathos-filled composition. She was still working them when I left. I couldn’t bear to watch any more. I did turn around to grab a couple shots of her from a respectable distance, so as not to disturb the artist at work.

In 1987 Life magazine published a story on the Damms, a homeless family in California. Mary Ellen Mark’s iconic photo of them in their car is the first image many people think of now when they hear her name. (You can own a limited edition silver print of this photo for a mere $10,000). In 1995 Life published a follow-up story about the same family, “The Sins of the Fathers”, also photographed by Mary Ellen, that was truly heart wrenching. The photos are classic Mary Ellen Mark masterpieces, but several of them still make me wonder if the family members ever had been in such physical attitudes or configurations before or since they met her.

For a long time afterward I was disturbed by Mary Ellen’s manipulation of her subjects, but my view has mellowed since then. It’s frustrating to be confined to any category, especially one so austere yet hard to pin down as “documentary photographer.” She has vast experience shooting on movie sets, beginning with Fellini’s “Satyricon” and probably a hundred more after that. She has watched the world’s greatest film directors at work, rubbed shoulders with actors from Olivier, Deneuve and Brando to the most unknown extras; from writers like Henry Miller to popular romance novelists. With all that proximity to creative storytelling it’s hard to imagine anyone not taking a few liberties. Finally, with such immense creative talent of her own now it’s more understandable to me that she would arrange her subjects to tell a more poignant story. Portrait photographers do it all the time, and part of her work might be better described as documentary portraiture.

Have I done anything similar in my own work? Absolutely, but I can’t recall ever being quite so blatant. Nor does my reputation stand on documentary photography, much as I love it. With advertising and even editorial photography almost anything can go; with news such things are not permissible. Annie Leibowitz manipulates her subjects; it is expected. But with documentary photography there is sometimes a fine line to navigate between truth and fiction. Relationships between people can easily be fictionalized by too much manipulation. I believe Mary Ellen Mark dances along that line often.

Invasion of privacy is another issue, yet in retrospect that pair may have been very pleased to be photographed by Mary Ellen Mark in any configuration at all. Whether her subjects ever see the result of her work is also up for grabs. Until recently none of my subjects from coal country ever saw my work, and I thought that was unfair. But there was no published venue for the photos, I had no darkroom back then and could not afford to have prints made to give them. (Digital technology has changed all that, and since launching this site I’ve made contact with one of the families in my coal country gallery – that of Rev. McKinley Underwood, from the Clovertown Church of God, images 35-39.)

Sometime around 2003 while writing my novel I made a trip back to Harlan County to try and find the Tollivers, but wasn’t successful. I couldn’t even find their old place, and finally someone who remembered them told me they had divorced. Too much time had passed. As for Mary Ellen Mark, she has worked in far too many places to backtrack, unless a story is as compelling as the Damm family’s. I found it amazing that National Geographic was able to find the Afghan girl Steve McCurry photographed 17 years after her photo became famous to half the world – which she knew nothing about.

But in the end it is people like Mary Ellen Mark, David Burnett and Steve McCurry (and many others who came before them) who open our eyes to worlds we wouldn’t see otherwise. They keep us in touch with our common humanity, and they continue to inspire me to do the best work possible. They all are legends for as many good reasons as the great photos they make.

So Mary Ellen, all is forgiven. I really do love your work – just give a beep next time.

Below: Mary Ellen’s assistant (left) takes a reading over her shoulder using a Pentax digital spot meter.

I enjoyed peeking over your shoulder as you reminisced.

The horizontal image of mourning man grabbed me. His posture, your crop, his expression. I’d love to see it B/W because of the classic and emotional aspect, a whisper in a cathedral filled with mourners…

Thanks, Dennis, for sharing.

Done – a good suggestion, as I think it works better that way too. It seems I began shooting color that day and switched to black and white, probably for that reason.